sarahHANDLER

Chinese art historian: Material culture - Furniture - Painting - Architecture

HOME | MAIN WORKS | EXCERPTS & MORE | SCHOLAR’S DESK | LECTURES | BIBLIOGRAPHY | ABOUT | CONTACT

Photo by Seth Affoumado

HOME | MAIN WORKS | EXCERPTS & MORE | LECTURES | BIBLIOGRAPHY | ABOUT | CONTACT

©2018 Sarah Handler

Powered by Barely Sober Media Partners, LLC

Santa Monica | Phoenix

SMALL USEFUL OBJECTS FOR A SCHOLAR’S DESK

The utensils of a scholar’s desk are not only necessary tools for writing and painting but also delightful objects. Sometimes they are miniature animal sculptures of real and imaginary beasts, each imbued with the breath of life.

Ink is made by dropping water onto an ink stone and then grinding a solid ink stick. Small vessels, sometimes animal-shaped, are used for dropping the water onto the stone.

These animal-shaped water vessels are functional and fun. They are like the lively animal weights that hold down the thin paper or silk when writing or painting.

The Scholar’s Desk

In his garden studio the scholar seated at his desk looks up from the book he is reading. Brushes, ink-stone, and water-dropper are arranged conveniently on his right. On his left there is an incense burner and cup of wine to create the proper mood.

Yang Jin, Portrait of Shi Xie,

1695, detail. ( Kaikodo Journal

XIX, 18)

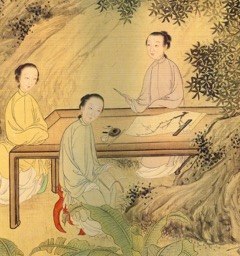

A large table has been carried out to the garden so that a lady can paint early spring plum blossoms. The rectangular ink-stick has been ground on the oval ink-stone. A weight holds down the paper.

You Shou & Wang Gong, The Female Disciples of Master Suiyuan, 1796, detail. (The Shanghai Museum)

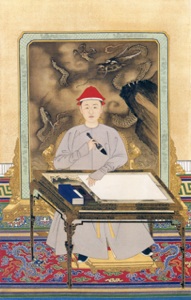

About to set brush to paper, the emperor is seated on an elaborate folding armchair in front of a dragon screen. The marble top of his ornate lacquer table evokes a mountain landscape and is a practical surface for painting and writing.

Portrait of the Kangxi Emperor in Informal Dress Holding a Brush, 1662-1722. (The Palace Museum Beijing)

The soft relaxed body and expression of a resting camel are sensitively conveyed in this miniature bronze sculpture. Water flows through its nostrils.

Camel water-dropper, bronze, possibly 13th century. (Michael Goedhuis, Chinese and Japanese Bronzes A.D. 1100-1900, 35)

The mythical qilin , sometimes compared to the unicorn, is a gentle beast that appears only during the reign of a benevolent ruler. Often it has a fleshy single horn that makes it unfit for war. It is a symbol of longevity, a wise administration, and illustrious sons. Water is drawn out of its body by inserting a tube in the hole on its back.

Qilin water-dropper, bronze, 15th/16th century. (Michael Goedhuis. 36)

Water is dropped from the tortoise’s mouth, its flow controlled by an air vent on the top of its back. The copper insets and swirling patterns on its surface are inspired by ancient bronze vessels, giving the dropper a much appreciated antique feel. The tortoise is a symbol of longevity, the north, and winter.

Tortoise water-dropper, bronze, 17th/18th century. (Michael Goedhuis, 28)

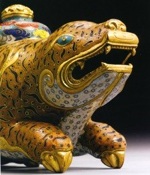

Exquisite workmanship and ornate decoration make this plump water-dripper fit for an emperor’s desk. The ferocious tiger is the king among beasts and powerful for warding off evil.

Tiger water-dropper, cloisonné, Qianlong (1736-95). (Sotheby’s London 11/9/2011.)

Bucolic scenes of small boys riding on the backs of water buffalo suggest a peaceful life free from everyday stress. This animal could be a rhinoceros or a water buffalo with one horn.

Ceramic water-dropper, 13th century.

(Kaikodo.)

Despite their small size these recumbent beasts are full of life and convey the essence of living creatures.

This lively qilin seems about to leap up and swiftly carry the scholar to his destination. Like many desk objects it is multi-functional.

Animal paperweights, bronze, 16th-17th century. (Michael Goedhuis, 27A,B.)

Scholar riding qilin brushrest/paperweight,

bronze, 16th century. (Michael Goedhuis, 32.)